Robert Mapplethorpe Exhibition the Perfect Moment at the Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center 1989

The Perfect Moment was never that. Non in Cincinnati, anyhow. Or non until the end.

When workers began unloading a truck full of Robert Mapplethorpe's lifework 25 years ago today, the exhibit already felt like a gathering storm, a drove of challenging photographs and difficult questions about sexual practice and sacrilege, fine art and obscenity, politics and polemics.

The prove, titled The Perfect Moment, opened on a chilly April morning in 1990, and amid the first people through the door of the Contemporary Arts Center were ix members of a grand jury who viewed the 175 photographs and accounted seven of them to be not only offensive, only criminal.

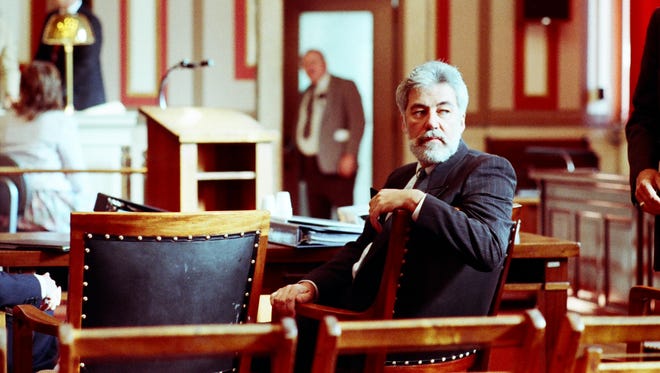

By that afternoon, the yard jury had handed down indictments against the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) and its director, Dennis Barrie. The indictments were the first fourth dimension in the history of the country that a museum and director were charged criminally for obscenity because of a public showroom.

The constabulary arrived and cleared the museum. Officers photographed the photographs. Protestors on the street held upward their arms in Nazi salutes and yelled "Sieg Heil." Men rolled on the street kissing each other in protestation.

Patrons were then let back in, just the process had already begun. At that moment, the city became a national phase for lawyers and free speech proponents and gay rights activists and family values supporters.

Eventually, the question of what is free speech communication and what is too much would exist heard in a Municipal Court room that usually passed judgment on things like shoplifting and bar fights. Later on a week of explicit and evocative photographs and skillful testimony, a jury went into its room for what was expected to be a long booty and a sure outcome.

The jurors came out two hours afterwards and shocked the earth.

Looking back 25 years afterwards, it would exist called a "beautiful disaster." But at the time, it felt similar half of that.

Mapplethorpe missed the drama. The artist had AIDS and died the year before the Cincinnati show at the age of 42. His exhibit was uniformly admired for its technical expertise and artistry. Most of the work consisted of even so lifes and nudes and portraits. Seven of the photographs were something else entirely.

These photographs were not difficult for the faint of heart. They were non hard for prudes. They were hard. They however are.

Five of the photographs were explicit images of sadomasochistic sex. Among them, a man urinating into the rima oris of another and anal and penile penetration with a finger, arm, bullwhip and cylinder.

The other 2 photographs showed young children – a boy and a girl – with their genitals exposed. Those photos were approved by their parents. The children were not involved in any sex activity deed.

All of the Mapplethorpe images were formally staged, an event which highlighted their graphic nature. In a review of the showroom, Time mag wrote of their "calm Apollonian framework for wild Dionysian content."

In 1990, the cultural and political climate made them even more onerous. At the time, the combination of art and sexuality and spoken communication were front page news. Much of this began on the floor of the United States Senate in 1989, when Senators Alfonse D'Amato (R-NY) and Jesse Helms (R-NC) went apoplectic over a slice of fine art titled "Piss Christ" which depicted Jesus Christ in a container of the artist'southward urine. The artist was Andres Serrano.

"This so-called piece of art is a deplorable, despicable brandish of vulgarity," D'Amato said. The senator was outraged that taxpayer money supported the art through the National Endowment for the Arts. "This is non a question of gratis speech. This is a question of corruption of taxpayers' money."

Senator Helms was more succinct. "I do not know Mr. Andres Serrano, and I promise I never run into him," Helms said. "Because he is not an creative person, he is a jerk."

If that was non the start of the "Civilisation War," it was an escalation. So Senator Helms saw the Mapplethorpe photos. The Perfect Moment was curated with $30,000 of support from the NEA. Helms was non a fan of the art, or Mapplethorpe, or seemingly his sexuality.

"This Mapplethorpe fellow," Helms told The New York Times in 1989, "was an acknowledged homosexual. He's expressionless at present but the homosexual theme goes throughout his piece of work."

Some of the work in The Perfect Moment depicted naked blackness men and naked white men. Sometimes they were posed together. For Helms, this was pornography. Worse than that, it was government-sponsored. "There is a big difference between 'The Merchant of Venice' and a photograph of two males of different races (in an erotic pose) on a marble-top table," Helms told the Times.

At that place was talk of eliminating the NEA. Helms introduced an amendment to ban government grants used to "promote, disseminate or produce obscene or indecent materials, including but not limited to depictions of sadomasochism, homoeroticism, the exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts."

Representative Dick Armey (R-Tex.) wanted the NEA to stop sponsoring art that was "morally reprehensible trash." He wanted guidelines installed that would "pay respect to public standards of gustatory modality and democracy."

Armey said that if the NEA did not agree to that, he would "blow their budgets out of the water" by showing all of his beau lawmakers the Mapplethorpe photographs.

At this fourth dimension, in 1989, The Perfect Moment was scheduled to run at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. With the rhetoric heating up, the fine art world blinked. The Corcoran decided to abolish The Perfect Moment.

Barrie, director of the CAC, remembers the exact moment he learned of the Corcoran'due south decision. He was at a museum leadership conference when the news was announced. At that place was, he said, a gasp in the room. "Then the guy side by side to me says, "I wonder who has it side by side?" Barrie told him information technology was headed to Cincinnati. To the CAC. The man had a 3 give-and-take response: "You are (expletive)."

When the Mapplethorpe photos arrived by truck on March 28, 1990, Cincinnati had a widely held and mostly earned reputation as one of the most conservative cities in America.

Hamilton County Sheriff Simon Leis Jr. was waiting for the photographs. In his mind, the photographs were smut, non fine art.

"Did yous see the photos? Did you encounter them? This was beyond pornography," Leis said this month. "When you put a fist upward a person's rectum, what do you telephone call that? That is not fine art."

Leis was the impetus backside the grand jury investigation and the indictment. And he had help.

In Feb of 1990, the Cincinnati group chosen Citizens for Customs Values did a mass mailing calling for "activeness to prevent this pornographic fine art from being shown in our city."

Bengals' tackle Anthony Muñoz and Passenger vehicle Sam Wyche thought the art should not see the light of 24-hour interval in their urban center. Robert Behler, a retired automobile dealer in Finneytown, said he did not believe in censorship "in a broad sense, just I firmly believe those photos don't suit with community standards."

Others wanted to back up the testify. Or the option to run into it. Or free speech. Or something.

A group of l people ate their lunch at Fountain Foursquare with brown bags over their heads to protest censorship. Jeff Stegman wore a handbag that said: "I'm embarrassed to live in Cincinnati."

Barrie was emboldened by the unanimous support of the 36-member board of trustees at the CAC. Barrie said the political climate made his decision easier.

"I didn't think there was any alternative only to stand upwards," Barrie said concluding calendar month from his home in Cleveland. "Nosotros are the art earth, we take to stand up upwards. If we don't, nobody volition."

But he knew he was in for some trouble.

The CAC made concessions. The exhibit would only be open up to people 18 and older. The photos deemed near controversial, labeled Portfolio X, would exist cordoned off and shown in a separate infinite.

None of that mattered on April 7.

At nine in the morning time, the doors opened and the grand jurors were among the commencement to come up through. By ii:30that afternoon, the thou jury announced the indictments. At ii:l, the Cincinnati Police arrived with a search warrant and cleared out the patrons. People on the street greeted them with "Sieg Heil" and "Gestapo go home."

The constabulary photographed and videotaped the exhibit and then re-opened the doors. That's when the chanting began: "Not the church, not the state, we determine what art is great." Followed past: "Simon Leis is the one who'due south warped, continue your hands off Mapplethorpe."

The metropolis took a beating. Mike Royko, columnist for the Chicago Tribune, wrote of the efforts to censure the art: "All they've washed is hype the exhibit and make Cincinnati await like a big rube boondocks, which I've never thought it was. Information technology's always struck me as a medium-sized rube town."

Omnipresence, defiance soared

The testify ran and was an unqualified success. Nearly 80,000 people came to the CAC in 50 days, a far greater number than in an average year then and at present.

In 1990, Aaron Cowan was a freshman at the Art University of Cincinnati. He was only 19, just he knew this prove was a big deal. "Information technology did feel of import," Cowan said. "It felt like a meaningful time."

Cowan said art needed to be protected in 1990, when it was harder to see things. Google did not exist and Facebook wasn't a thought. The starting time photo to ever appear on the Globe Broad Web was posted in 1992.

"The concluding matter I wanted back then was less accessibility," Cowan said. "I don't demand to agree with the message, but I need to be able to decide."

Cowan, now the director of fine art galleries at DAAP, the University of Cincinnati's College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning program, has come to appreciate art now more than e'er.

"Art can be an agent for change. Information technology'due south a public record. It is a reflection of what is power and what is counter to that," he said. "Information technology give people who feel marginalized the ability to speak, to share their view."

Cowan did not encounter the photographs on display behind the curtain at CAC. He went and saw the 168 photographs and and so stopped. Maybe he wanted to brand a point. If just to himself.

"That was a determination that I made," Cowan said. "I fabricated that choice. Nobody should make information technology for me."

It was after the evidence airtight, after the crowds went home that history would happen. The prosecution of Barrie and the CAC began at the end of September.

A jury of eight people in bourgeois Cincinnati was going to draw a line in the sand. Art would be more "decent." Or art would be left lonely.

Oddly, this would happen in a Municipal Court room, a place that lacks grandeur and gravitas. Typically, people with unpaid tickets sit side by side to the boozer and disorderly who sit down next to the guy who peradventure stole a handful of Slim Jims from a convenience shop.

Not in this case. Costless speech would be debated here. The jury would decide what is criminal and what is art.

Frank H. Prouty Jr., assistant municipal prosecutor, began his opening argument by graphically describing the five sadomasochistic images. Then he spoke of the jury's place in history. "You have a unique circumstance. There has never been a museum charged with obscenity. Yous have the opportunity to decide on your ain where you draw the line."

Prouty was in a unique position. His job was to become a prosecution. But his parents were teachers and art lovers. On the legal problems he argued loudly and effectively. He said the jury should simply see the seven controversial photographs and not the entire show. The estimate agreed. He said the CAC was a gallery, and non a museum, which meant it would not take many free oral communication protections. The judge agreed. Both of those were significant legal victories.

H. Louis Sirkin, the attorney representing the CAC and Barrie, said at the time of the decisions: "It'due south and so intellectually wrong, it's incredible." Sirkin continued: "All I can tell you is, if we get an acquittal, we're absolutely brilliant."

When Prouty stood to make his instance to the jury notwithstanding, all he did was show them the photographs. Then he chosen police officers to the stand up and asked them if those were the photographs hanging at the wall at the CAC. Then he was finished.

This week he looked back at the example and said he was but doing his job. Setting customs standards is upwards to a jury, not a lawyer. It was an interesting tactical choice, and an honorable ane.

"The obscenity consequence, the pictures must speak for themselves. The jury is the community," Prouty said. "They set the standard. Let them make the decision."

Then the defense began. Left with just the seven photos, Sirkin would need to recharacterize the photos not equally "sexual practice acts" but as "figure studies." Information technology was going to be a long haul.

But Sirkin knew he was not without hope when the jury saw the photos for the kickoff time. Each picture was passed around the jury box, moving from hand to mitt; the jurors took just a few seconds to await at each one. No expression registered on their faces.

"Isolating the seven photos was very disappointing," Barrie said this month. "I think, oddly enough, it was a turning point. The jury knew there were more photos. They knew there were 175 images and they felt information technology was wrong to not run across them. They felt excluded."

The fact that the jury could only see the seven photographs also forced the defence force to assail the event of what is fine art without blinking. They had no choice. Rather than hide from the difficult images, Sirkin brought them forepart and heart and made the unabridged trial nearly them. He never blinked.

A succession of defence force witnesses all said the aforementioned matter: The Mapplethorpe work was art.

Jacquelynn Baas, director of the University Art Museum at the University of California at Berkeley, testified that the 7 photographs had serious artistic value in terms of how the pictures were composed and about what Mapplethorpe was maxim. Discussing one photo depicting anal penetration with an arm, for instance, Baas noted the tension between the beautiful quality of the photograph and the "brutal nature of what's going on in it."

"They are pictures with serious artistic intent," said Janet Kardon, the former director and curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. She and Mapplethorpe created the show. "(Mapplethorpe was) very attentive to lighting, arrangement within a picture, texture of skin, the same criteria he would utilise when he would do a flower."

Robert A. Sobieszek, senior curator of photography at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House in Rochester, N.Y.: "I don't believe art can be pornographic."

Do yous think these photos are art?

"Aye, I do," said Sobieszek. "They reveal in a stiff, forceful way a major concern of the artist, a troubled portion of his life that he was trying to come to grips with. A search not unlike Van Gogh painting a portrait of himself with his ear cut off."

And and so Sirkin rested. He put his faith entirely in the jury.

"To the credit of the jury, they really listened. Artists are hither to challenge u.s.," Sirkin said this month. "These jurors were not familiar with the exhibit or even this museum. Only these people knew that was a museum. That if y'all wanted to go run into it, you should be able to see it. And if you don't desire to run across it, fine, merely don't go."

The jury was many things. It was not, however, a group of aestheticians.

They were a secretary from Forest Park, an electrical engineer from Delhi Township, a Procter & Take chances Co. export coordinator from Mount Healthy, an athletic goods saleswoman from Cincinnati, a warehouse managing director from Blue Ash.

Six of them were married, and all 6 had children. 1 of them had 4 grandchildren. Three had been to college.

They were Baptists, Catholics and Methodists. About of them had visited the Cincinnati Art Museum and Cincinnati Museum of Natural History. I had been to the Taft Museum. One of them contributed to the Fine Arts Fund. None had been to the CAC.

Ane said he didn't much like coming downtown because of the traffic. None of them had attended the exhibit.

With this jury and with the court decisions regarding the photographs and the judge'due south ruling that the CAC was not really a museum, the deck looked fairly stacked for a conviction. Nigh court observers were certain of two things: This would take a while, and things did non expect skillful for Barrie and the CAC.

After the closing statements from the lawyers, the jurors were given the instance at 1:05 pm, then spent an hour at lunch, returning to the jury room at 2 p.thou. At 4:ten p.m., they told the bailiff they had a verdict.

Dennis Barrie and the CAC were acquitted on all charges.

The Mapplethorpe showroom was non obscene.

Barrie could not believe information technology. He was facing a fine and jail fourth dimension. Even though nobody really thought he would ever see the inside of a prison cell, a conviction would have been chilling.

The jury, representing all of greater Cincinnati, said that would non happen hither.

None of them seemed to similar the images. But none thought anybody should tell somebody else what fine art they tin and cannot see.

"The pictures were not pretty. No doubt about it," said James Jones, one of the jurors, equally he tried to put the decision into perspective in the hours later on the trial. "But, as information technology was brought up in the trial, to exist art, it doesn't have to be pretty."

Barrie saw the celebrated significance from the onset. "This is a great day for this urban center, a slap-up day for America. They (jurors) knew what freedom was all nigh. This was something important. A major battle was fought hither, for the arts, for creativity. I'g glad the system does work."

The consequence had been closely watched by museum directors and legal scholars nationwide. "I am truly astounded," said David Ross, manager of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, where the traveling Mapplethorpe exhibit went afterward Cincinnati. "I had expected the jury to convict. I am more proud to be an American today."

Raphaela Platow is the managing director of the CAC at present. Two Mapplethorpe photographs hang in the boardroom in that location. A point of some pride, just all the same not a public showing. Platow said the jury should be applauded today.

"Information technology was a keen moment I call up just for freedom of voice communication nationwide," Platow said. "In the end, a group of layman decided that it was totally OK for people to decide on their own if they wanted to meet the show or non. I thought it was simply a actually remarkable democratic endeavor backside this determination."

And ultimately it was adept for the CAC. "I think it elevated the establishment in a style, because it fought for its right to be a catalyst for what's new and what's next and what's important and what people are thinking almost and what's going on in civilization," Platow said.

Sirkin, the defense attorney and national First Subpoena specialist, is not sure if the acquittal really changed things in the Cincinnati art community. He said the trial itself was frightening. "I think information technology instilled fright in art institutions in the city and art patrons in the urban center," Sirkin said this month. "I think some of them thought: 'Holy B, that could happen to me.' Information technology had a spooky effect. They began to self-censure."

Tamara Harkavy, CEO and founder of ArtWorks which creates art and artists, says the trial feels like longer than 25 years ago. Looking dorsum at it, she chosen it "beautiful disaster." She said 10 years passed before some people in the local fine art community found their basis again. But they did, and when they did, they had a improve perspective.

"People looked at failure differently. They looked at risk differently," Harkavy said. "I but spent 90 minutes in the lobby of the CAC. It's magnificent."

Barrie thought that Cincinnati, despite its conservative reputation at the time, might have been a perfect place for a trial about art and spoken language. Cincinnati, he said, is a place where people think they should be immune to brand their own decisions. And the jury proved it.

"I think it was a tipping indicate for Cincinnati," Barrie said.

And what did he practise that night, with his colleagues at the Gimmicky Arts Eye? "Oh that was a good night. A fun night. We went out and got drunkard. It was Cincinnati."

No museum or manager has ever been charged since.

0 Response to "Robert Mapplethorpe Exhibition the Perfect Moment at the Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center 1989"

แสดงความคิดเห็น